Earlier this month, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) delivered its final report. When the TRC was established in 2008, it was given the mandate ‘to reveal to Canadians the complex truth about the history and the ongoing legacy’ of Indian Residential Schools, church-run institutions that operated in Canada from the 1870s up until the 1990s. Approximately 30% of Aboriginal children (in Canada, known as First Nations, Inuit and Métis people) were removed from family, culture and land and placed in Residential Schools.

The TRC’s findings included 94 ‘calls to action’ – in areas including child welfare, education, language & culture, health, justice and reconciliation. Four of these calls to action related to museums and archives (see no’s 67 to 70 on page 8).

Calls to action no’s 69 and 70 refer to Aboriginal peoples’ ‘inalienable right to know the truth about what happened and why, with regard to human rights violations committed against them in the residential schools’. What is this right to know the truth?

People who have been subjected to human rights violations have a right to know the truth, as part of their right to an effective remedy. The right to know the truth even has its own day – 24 March – as proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in December 2010.

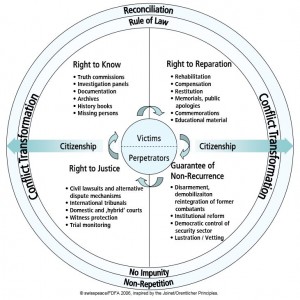

In international law, the right to know the truth is most commonly referred to in connection to enforced disappearances and action to combat impunity. It is enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and in the Updated Set of Principles for the Protection and Promotion of Human Rights through Action to Combat Impunity (2005), more commonly known as the Joinet/Orentlicher Principles.

These Principles raise fundamental issues for archivists, and for any individual or organisation with records that bear witness to violations of human rights. The right to know is closely tied to the ‘duty to remember’. For the truth about injustices and violations in the past to be established, and dealt with, the records need to be preserved, and made accessible.

Archives and records are closely related to human rights, justice and reconciliation. This fact is increasingly being asserted by the archival profession. Currently, the Human Rights Working Group of the International Council on Archives is finalising its Basic Principles on the Role of Archivists. This document states that the enforcement of human rights and fundamental freedoms is strengthened by the preservation of archives and the ability of individuals to gain access to them.

Forgotten Australians’ fight for justice and recognition, of which access to records is a crucial element, can be seen in the context of global human rights and the ‘right to know’. Indeed, a number of the submissions to the Senate’s inquiry into children in institutional care in 2004 invoked notions of human rights:

I hope that every state ward and any child that’s spent time in the so called care of the child welfare department speaks out and tells of the horrific treatment they received at the hands of these staff employed to care for us … Someone must be made accountable. It must be recorded and known that nobody needs to be treated in such a dreadful manner … I hope that you can compile all our stories and know it’s a piece of Australia’s history that is so shocking it needs to be looked at closely and questioned (Submission 271).

In 2012, the advocacy and support organisation CLAN made a submission to the United Nations Committee against Torture, declaring that children in Australian institutions were denied their basic human rights, and Australia’s history of abuse, neglect and maltreatment of children in institutions amounted to the UN’s definition of torture, and of ‘cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment’. Representatives of CLAN addressed the Committee against Torture in Geneva in 2014.

In 2012, in its Submission on Australia and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Australian Human Rights Commission included information about Care Leavers and past abuses suffered in out-of-home care. This year of course, since the tabling of The Forgotten Children report, the Commission has been more prominently concerned with abuse and rights violations that are happening right now.

Further reading:

Nathan Mnjama, ‘The Orentlicher Principles on the Preservation and Access to Archives Bearing Witness to Human Rights Violations’, Information Development August 2008, vol. 24 no. 3, 213-225, doi: 10.1177/0266666908094837

‘Principle of the Right to Know the Truth and the Right of Reply’, Exposure Draft Position Statement: Human Rights, Indigenous Communities in Australia and the Archives (prepared by Dr Livia Iacovino, Professor Eric Ketelaar and Professor Sue McKemmish on behalf of the ‘Trust and Technology: building an archival system for Indigenous oral memory’ project).

A conceptual framework for dealing with the past, Swisspeace, 2012.