Once My Mother is a film by Sophia Turkiewicz from 2014. In the film, Sophia explores her troubled relationship with her mother, Helen. Deported from Eastern Poland during World War Two, Helen survived forced labour camps, and a perilous journey through Siberia, Uzbekistan and Persia to end up in a refugee camp in Africa – where Sophia was born.

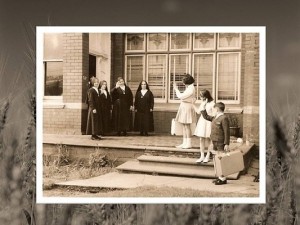

Orphanage, Adelaide.

Courtesy: Once My Mother website.

Helen came to Australia as a single mother with her little girl, with no English and no formal education. When Sophia was 7 years old, her mother placed her in an orphanage in Adelaide. Sophia stayed there for ‘two bewildering years’ until Helen was able to bring Sophie to a new home, with her new husband. In this film, Sophia looks back on her childhood and tries to learn more about Helen’s life, while her mother battles dementia.

This wonderful film is screening this weekend on ABC1, Sunday 26 July 2015 at 2.40pm.

Last year, on 16 October 2014, I was part of a very special evening at The University of Melbourne, where the film was shown, followed by a panel discussion featuring Sophia Turkiewicz and the film’s producer, Rod Freedman. The interdisciplinary panel, chaired by Dr Julie Fedor from the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, featured Dr Malgorzata Klatt and Dr Erminia Colucci from the University of Melbourne, and Sophie Skarbek, President of the Polish Siberians’ Association in Victoria. Sophie Skarbek’s life story has some similarities with Helen’s – Sophie was also born in Poland – in April 1940, she was exiled to Kazakhstan with her mother, brother and aunt – her father was killed at Katyn. After ten years as a refugee, she arrived in Australia in 1950, where she later trained and worked as a psychologist.

Another speaker on the panel was Dr Alexandra Dellios, whose response to the film explored how stories like Sophia’s complicate and challenge the public history of post-war mass migration to Australia. She said:

We are all familiar with migrant success stories—those post-war migrants made good; further, we are all familiar with the idea of the socially mobile second generation. What Australian public history and popular culture is less familiar with are stories of single women, specifically unmarried mothers in post-war Australia. These histories are not just individual, they are not just familial—they are also a potent means to explore the running of the post-war migration scheme and to explore some of the myths that surround that scheme, and the image of Australia as proffering a national cuddle to those most in need.

A full transcript of Alex Dellios’ presentation is reprinted below.

The panel also included author Frank Golding, who shared his personal response to the film as another ‘orphan of the living’, having been placed in ‘care’ at the age of 2. Frank said:

Like Sophia, I heard my mother say, ‘I’ll come back and get you one day’. And like Sophia, I sat and waited, and waited some more, watching for the tram that would bring her back. Eventually, like Sophia I lost faith in my mother – and in my father. I stopped believing. Unfulfilled hope hurts too much in the end.

When our reunion did eventually occur it was not easy to forgive. Maybe the elastic bands of kinship had stretched beyond snapping point. How could you know the persons who had given birth to you when they had so forsaken you? Is it possible to be a good son when you have so much forgive?

Frank’s whole piece can be found on his blog.

As I recall, I spoke after Frank – a hard act to follow! But here is a transcript of what I said at this event, talking about the Find & Connect web resource and its information relating to Homes that accommodated migrant children:

Cate O’Neill’s response to ‘Once My Mother’, 16 October 2014:

I work on a project that is helping to document the history of children’s institutions in Australia – the Find & Connect web resource has information about the ‘archipelago’ of orphanages and children’s homes that existed, and about the organisations – government, charitable and religious – that ran these homes. [Joanna Penglase, author of Orphans of the living, used the term ‘archipelago’ in an oral history interview in 2010.]

Find & Connect is funded by the Australian government, as part of its response to the Apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants in November 2009. There are many people who grew up in ‘care’ who are searching for records about their childhoods, so they can make sense of their past and who they are, so they can take legal action for crimes committed against them, so they can restore connections with lost family members … The website is also there to raise awareness about this history and make it possible for more stories to be told.

A book has just been published that talks about the institutionalisation of women and children in Australia as a Silent System. We’re currently going through a process in Australia where the history of these institutions, and more importantly, the histories of the people who lived in them as children, is starting to emerge from this silence and secrecy.

One thing that struck me when I first saw Once My Mother is that the stories of migrant families who were drawn into the ‘child welfare’ system after World War Two are even more silent than those of the ‘Forgotten Australians’ from Anglo backgrounds. Sophia’s film makes a vital contribution to this emerging historical area.

The families in the child welfare system were vulnerable – because of factors like poverty, mental illness, addiction, violence – the particular vulnerabilities faced by migrants is an area that is yet to be explored in any depth.

We know that there were particular institutions for migrant children that were established in the post World War Two period – these were associated with particular religious orders.

Antonian Institute, c.1960.

Source: Daughters of the Divine Zeal.

The Daughters of Divine Zeal ran the Antonian Children’s Home in Church Street, Richmond (1959-1979). Most of the children who lived there were from Italian families.

Providence Children’s Home in Bacchus Marsh was established in 1957 by the Catholic Dutch Migrant Association.

Although Sophia lived at Goodwood Orphanage, there was a Home in Adelaide specifically for Polish children – St Stanislaus House (1956-1978) in Royal Park was run by the Sisters of the Resurrection (who are based now in Essendon, Victoria).

St Stanislaus was established due to the efforts of Polish migrants in Adelaide. The community arranged for Polish American nuns from the Congregation of the Order of the Sisters of the Resurrection to be brought out to Australia to run the Home, which was for orphans, children from ‘broken homes’ and children whose mothers couldn’t care for them because of illness or work requirements.

St Stanislaus House was actually demolished in 2012. We only found out about this because a woman called Irene got in touch with our website – she’d lived there as a child. After getting the email from Irene, our historians in Adelaide went off on a quest to find records, photographs and information about St Stanislaus.

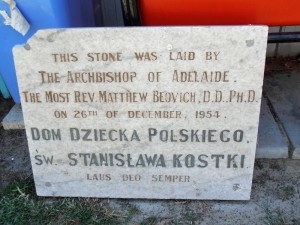

The only photographs we have of this Home are taken from Google StreetView (luckily the image hadn’t been updated at the time we learned about the demolition) and from a serendipitous encounter our researchers had with John, a bloke who lived across the road. He actually rescued the Foundation Stone from the developers and we have a photo of it on our website now. John shared his memories of having lunch and sometimes dinners at the orphanage when his parents were working late. He used to hang out with kids from the Home and they attended the local Catholic school together.

Courtesy of Gary George.

I’m sharing this story of St Stanislaus, partly because I thought the Polish angle would be of interest to many of you today, but also because it’s a great example of why the Find & Connect website is important, and what keeps our team inspired to do our work.

The stuff on our website is there to provide some kind of scaffolding for people to build or maybe reconstruct or repurpose their own life stories. Everyone needs this structure to be able to tell stories, and this structure is particularly important for people who grew up away from their families, or who have lost connection with their childhood or their past – through migration, through trauma, through accidental loss.

Finding and documenting these places is something our team of historians hold very dear – in the words of our SA historians, Karen George and Gary George:

Buildings which served as Homes for children were the site of many childhoods. They are places of importance to the identity of Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants. St Stanislaus is now gone. There is no indication that children once lived there. Through the web resource we will do all we can to make sure these children’s lives are remembered.

Once My Mother is just an amazing example of storytelling, and the interactions between personal memories, family histories and world events.

Alexandra Dellios, ‘Generational storytelling and public history: a response to Once my Mother’, 16 October 2014:

I want to speak to silences in official histories, and the emerging role of generational voices in amending these silences. Individual stories of migration are not new to Australian popular culture or to public history. We are all familiar with migrant success stories—those post-war migrants made good; further, we are all familiar with the idea of the socially mobile second generation. What Australian public history and popular culture is less familiar with are stories of single women, specifically unmarried mothers in post-war Australia. These histories are not just individual, they are not just familial—they are also a potent means to explore the running of the post-war migration scheme and to explore some of the myths that surround that scheme, and the image of Australia as proffering a national cuddle to those most in need. In Once My Mother, Sophia Turkiewicz referred to the lies of historians: “the chapter on your story is missing” she says of her mother’s incredible trials during and after the war. We need these stories, not only to complicate popular success stories, but because they are national and international histories. I would also argue that the history of the post-war Polish experience, in all its diversity, is missing from the public record in Australia.

When Australia first started accepting Displaced Persons as part of the newly formed International Refugee Organisation and their settlement scheme, the government sought single, healthy men who were able to perform manual labour. The wider post-war immigration scheme was driven by this eye to employment in primary industries and manufacturing. Only from June 1948 were family units sought. Not single mothers. In February 1949, Minister for Immigration Arthur Calwell agreed to the recruitment of widows and unmarried mothers, but he specifically ordered that no publicity be given to their recruitment. To the government in post-war Australia, such women were a “burden”. The government’s promotional material presented assimilable Baltic families—blonde and blue-eyed—and sprightly young male labourers as a positive addition to post-war Australia and the main focus of the Government’s initial scheme. Women were rarely valued as part of this national vision. Social workers too wrote condemning reports of single women with children—they represented economic and social failures to assimilate.

Initially, only married women were eligible for accommodation in Commonwealth Holding Centres; single women and single women with children were mostly excluded under the government’s policy—although we have multiple examples of single women with children accommodated in these centres. But due to the burden of rent and the pressure to find employment and move out of the centre as soon as possible, many single women were forced to place their children in institutions or Catholic homes, while they found work and affordable accommodation. While this image of family separation is missing from the popular image of the post-war immigration scheme, some historians have paid it attention—Ann-Marie Jordens, Catherine Panich and Michael Cigler all refer to family separation as an unfortunate (and cruel) facet of the government’s immigrations scheme. Despite some recognition by historians, the public presence of personal stories of separation are an important counterweight to the public narrative. They also bridge the gap between academic histories and other forms of storytelling.

The role of generational voices in amending these silences, I believe, has become incredibly important. Academics and some pop culture have pointed to the more assertive and socially mobile second generation, those children of post-war migrants or those that arrived as children. They became more vocal from the 1980s, particularly in the Arts. And films from this time like Silver City moved us beyond the journey of migration, and posited migration and adjustment as a life-long process that extends beyond initial settlement, and one that involved looking both forward and backward. But why is this an exercise for the second generation—to represent these journeys, to explore them? Also, how and why do we draw on our parents’ stories? And to whom do we have the obligation to “get it right”?

The act of “going back” to a place which you’ve only visited through the stories of parents encapsulates this relationship—and I was particularly struck by the curiosity, sense of discovery and eventual familiarity with which Sophia seemed to move through those Polish spaces that contained so much meaning [for her mother].

I myself have tried to understand my parents’ and grandparents’ lives through the prism of their war-time experiences and migration. But as I’ve indicated, this is more than an insular and meditative process: it’s about situating parents’ and your own stories within wider context, it’s about attributing significance and new meaning, attempting to explain inexplicable horrors, and understanding impossible choices. Part of this task is to explain ourselves, as Sophia says: “they’re my stories. They tell me who I am.” Academics have spoken to memories of trauma and pain as generational. I’d also like to highlight the importance and power of public history and recognition, the collaborative need of the second generation to share publicly and have these idiosyncratic stories be part of wider narratives.

Rene

July 24, 2017 9:59 pmHard to comprehend the mother having to leave her 7 year old daughter and then the subsequent trauma and heartbreak. Thank you for documenting Australia’s history of children in migrant care.

Alexandra Dellios

July 24, 2015 4:30 pmThanks Cate! There’s some important research to be done here around the experiences of child migrants in care, and Find & Connect are doing some brilliant work. Some of your readers might also be interested in an ARC research project currently being undertaken by Prof. Joy Damousi and others: “Child Refugees and Australian Internationalism from 1920 to the present”: http://shaps.unimelb.edu.au/research/projects/fitzpatrick-laureate-fellowship

Cate O'Neill

July 24, 2015 3:01 pmThis afternoon, I edited this post so that it now includes the text from another fantastic presentation from the panel in October 2014. Thank you to Dr Alexandra Dellios for sharing her work!