This blog post is to share some good news about newly-available records at the National Archives of Australia (NAA) in Canberra. The records relate to the payment of child endowment to children’s institutions by the Commonwealth government. These records have become accessible as a result of advocacy by Care Leavers Australasia Network (CLAN), who successfully made the case to the NAA that these child endowment files are highly significant and of huge potential value to people searching for evidence of their time in ‘care’.

First, some background about child endowment in Australia. A national child endowment scheme was introduced in 1941, entitling every family in Australia to a 5 shilling per week payment (tax-free and not means-tested) for each of their children, excluding the first-born. This social reform was established partly to ease economic pressure that Australians were experiencing during the years of World War Two. It also had a lot to do with encouraging larger families and addressing the birthrate, which had been declining since the 1930s depression.

Even before the passage of the first child endowment legislation, it was apparent that there were anomalies in the scheme. In the bill’s second reading, ALP member Reg Pollard argued that the exclusion of state institutions was a distinct injustice, and would result in ‘unfortunate discrimination between the children of well-to-do parents’ who were eligible to receive the benefit, and children who were living in Commonwealth or State institutions.

It was also unclear whether the payments applied to Aboriginal children living on missions. State governments asked why a ward of the State child boarded out to a foster mother could be entitled to child endowment, while a child living in a state institution was not. Graziers also lobbied the Commonwealth government, saying that they were maintaining the children of Aboriginal people working on their stations (see NAA: A432, 1942/316).

The government responded to these criticisms by amending the Child Endowment Act in 1942 to extend the benefit to children in government-run institutions and to Aboriginal children on missions.

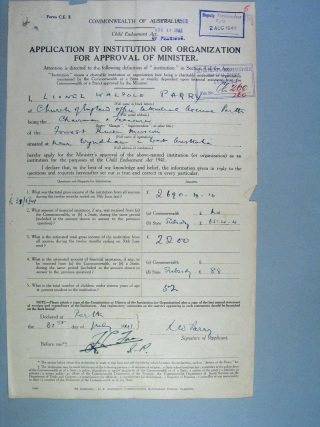

When child endowment was introduced, many organisations – like orphanages, children’s homes, babies’ homes, institutions for disabled children – applied to the federal Department of Social Services to be approved as ‘institutions’ for the purposes of child endowment, so that they could receive the weekly 5 shillings for every child they were maintaining. And this led to the creation of records – records such as application forms and supporting documentation supplied by the institutions to the Department; correspondence between the Department and institutions; financial records documenting the payments to institutions, etc. A collection of these records has survived and is held by NAA in Canberra.

For many years now, Care Leavers have focused on the child endowment payments by the Commonwealth to children’s institutions in their lobbying efforts. They argue that, even though children’s institutions were run by state and territory governments, churches and charities, the Australian government was nevertheless responsible for these children, evidenced by its financial support through child endowment payments. Care Leaver advocates claim that these payments undeniably facilitated the system of institutional care that caused so much harm and lasting damage to so many, and therefore, the Australian government had, and continues to have, a duty of care towards people who were in Homes as children; the responsibility does not solely rest with the states and territories.

‘It is disingenuous for the federal government to say, “We had no part in this,” because in fact it did.’

(Submission to the Senate inquiry into the Implementation of the Recommendations of the Lost Innocents and Forgotten Australians reports, 2009, quoted in Lost Innocents and Forgotten Australians Revisited, p.10).

CLAN has used child endowment in its advocacy, lobbying the Federal Government to introduce a national independent redress scheme for institutional abuse, and referring to it in its submission to the United Nations Committee against Torture in 2012:

‘By the Commonwealth Government providing child endowment in the form of a monetary contribution to all of these Homes and not ensuring their wellbeing, the Commonwealth Government is just as complicit in the abuse as State Governments.’

This advocacy has also included requests for more information about what child endowment records were held by the NAA. Following the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families and the ‘Bringing them home’ report in 1997, the NAA re-examined child endowment records in its collection and discovered that these administrative and financial records were a wealth of information about the children and families living on missions. The NAA’s name indexing project following ‘Bringing them home’ captured information from the child endowment files relating to Aboriginal missions and made some of them available to the public in digital form.

Despite these efforts by NAA, many more files relating to child endowment in its custody were very difficult to access, as they were unlisted. Following public pressure and advocacy, the NAA embarked on a listing project in mid 2016 to capture the Title and Date Range of these unlisted items. This work revealed that there were hundreds of files relating to payment of child endowment to children’s institutions. In October 2016, new data about these 566 files were loaded onto the NAA’s RecordSearch database.

These files were examined and given an open access status, so they are now available to the public, but only in the NAA’s Canberra reading room.

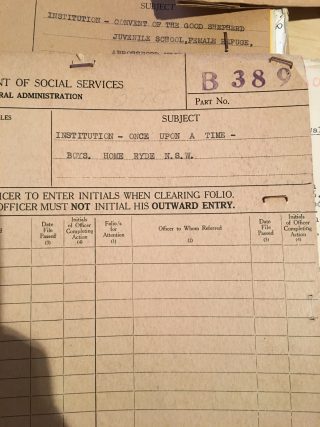

Earlier this month, I had the opportunity to examine around 45 of these newly-opened child endowment files. Even in this small sample, there was a huge amount of information that will greatly improve many entries on Find & Connect. I also found a couple of ‘new’ Homes that we don’t yet have on Find & Connect (including the quaintly-named ‘Once Upon A Time Boys’ Home’ in Ryde, NSW).

My quick survey of the records revealed that:

These records are highly significant sources of information about the administrative history of many children’s institutions. Institutions provided documents like annual reports, financial statements and publicity material with their applications for child endowment, containing valuable contextual information. Staff from the Department of Social Security also visited institutions – mostly to inspect their administration of child endowment payments, not to check of the wellbeing of children – and their reports contain descriptions of institutions and their recordkeeping systems.

The names of children living in institutions appear frequently throughout the records. From time to time, children are named (and other identifying information is provided such as date of birth, name of parent/s etc) when there was a discrepancy in child endowment payments that the Department was trying to resolve. Potentially, these child endowment records could provide some people with the only documentary evidence of their time in ‘care’.

What’s next? The Find & Connect project will report back to NAA about the findings of my quick research trip to Canberra, as well as sharing information with Care Leaver groups like CLAN, the Find & Connect support services, the Child Migrants Trust and Link Ups. We will recommend that these records be indexed and/or digitised so that their accessibility can be further improved. There is also a need to consult with Care Leavers about any further work to make these records more accessibile, so that it is provides maximum benefit to Care Leavers, and also takes into account the important issue of privacy.

Here are the details of the newly-available child endowment records, which are listed on the NAA’s RecordSearch database:

Series Number: A885

Title: Correspondence files, single number series with ‘B’ [Child Endowment] prefix.

Another way to browse the list of Titles of these files in this Excel spreadsheet.

A885 Child endowment items on RecordSearch as at 14 Oct 16

Picture Sources:

1. NAA: M4294, 3/1. [Personal Papers of Prime Minister Holt] Holt with a group of children after he introduced the Child Endowment legislation and was pronounced the ‘Godfather of a million children’.

2. NAA: A885, B203. Institution – Forrest River Mission, 1941-1969

3. NAA: A885, B389. ‘Institution – Once Upon a Time – Boys’ Home, Ryde, NSW’

geoffrey meyers

July 4, 2018 7:09 amThis makes you wonder why the employees over all these years kept telling us careleavers that there were no records of us being in care.Were these employees telling the truth or were they just too lazy to look for these records.Maybe this was another form of keeping the truth from us and covering up those terrible crimes of abuse,sexual abuse,physical abuse,physiological abuse and torture.

Leonie

July 2, 2018 12:34 amThanks heaps Cate & the FandC team ✅for keeping Care Leavers up to date on the Child endowement records

It is just wonderful news that there is another avenue for CLs to get records or info about the Orphanage, , Children’s Homes or Mission s they were in

What a find another Once a Upon a Time – Boys Home in Ryde NSW Any photos of this hidden Home ?

Let us know if CLAN can assist in any way

Hooroo

Leonie Sheedy